Homogeneity lends itself to utopia and dystopia both. The idea that humanity would eventually produce enough to fulfill everyone’s needs led to Star Trek and to Francis Fukuyama, to HG Wells and Karl Marx. But the idea that everyone’s needs can be fulfilled comes inherent with the degradation of culture and purpose: think Brave New World, Harrison Bergeron, The Giver.

The modern NBA is balancing on the same blade.

On April 16, Nick Nurse was discussing positionless basketball and said that he won’t be happy until everyone on the court is 6-foot-10 and “can drive and shoot the three and pass it and we can switch everything on defense.”

That may describe Nurse’s basketball utopia, but there are multiple reasons why it doesn’t exist. Of course, there aren’t enough such players to gather a full lineup’s worth on one team. Beyond that, the minute among us have some advantages that lurk beneath the surface; the league would be a worse place without undersized guards scampering around, winning basketball games. There’s a reason six-foot-nothing players remain a dime a dozen in the league. They’re damn good. It’s possible that’s not in spite of their height, but occasionally because of it. An NBA where everyone looks the same may be more dystopia than utopia.

Samson and I are both very short. Could have something to do with one of the meanings of Minute Basketball. So we thought -- who’s the shortest writer we know? Let’s bring Joe Wolfond into the mix. Ha. Just kidding. He’s one of the best and smartest people out there, let alone writers, so we at Minute Basketball could not be more excited to offer you Minute Basketball feat. Joe Wolfond: Short Kings.

Wolfond - The Low Ground

In combat, having the high ground is a massive strategic advantage, so much so that some consider it tantamount to victory. Generally speaking, the same is true on a basketball court.

Having a height advantage over an opponent presents myriad ways to attack them. You can shoot over them with a clear field of vision, back them under the basket to drop in an unimpeded layup or dunk, or peer past them to scan the whole floor for the best available pass. Even if one of those options produces a miss, you’ll probably have a decent chance to grab the rebound.

Basketball naturally selects for size. That’s just a consequence of a game in which the objective is to put a ball through a cylinder that sits 10 feet above the ground. But while elevation wins most wars in the NBA, plenty of battles can be won from the low ground. Doing so simply requires a special blend of skill and cunning. Certain things will always be out of reach from that position, but there are plenty of advantages you can leverage by virtue of being closer to the floor.

I grew up, as I imagine many diminutive basketball enthusiasts of my generation did, holding a special reverence for the likes of Allen Iverson, Damon Stoudemire, Earl Boykins, and that outlier of outliers, Muggsy Bogues. Admittedly, Muggsy was a little before my time, but I was always tangentially aware of him. (I liked to play as the Hornets with him and Larry Johnson in NBA Jam, and I trusted the Monstars' eye for talent when they chose to steal his in Space Jam. I even got to watch him finish his career as a backup for my Raptors.) You couldn't follow the NBA and not have at least a passing familiarity with his historically improbable career.

Watching NBA basketball is an exercise in object relativity. Because the vast majority of the league’s players are anomalously tall, and because you mostly see them in relation to each other, you don’t fully register just how anomalously tall they are. Point guards who would tower over me can look puny on an NBA court. At 5-foot-3, Bogues looked like a toddler skittering impishly around the shins of grown-ups.

Sure, that came with limitations. And yeah, Michael Jordan once taunted him in a playoff game by calling him a midget and daring him to shoot. But Muggsy knew who he was, and what he could and couldn't do. What he could do was burrow through the smallest crevices to find space, run laps around opponents in the open floor, and sling bounce passes beneath the prying arms of defenders. Also, nobody could do a damn thing to push him off the ball. Which makes some sense when you consider the short distance his dribble was traveling between hand and hardwood. Perhaps it’s no wonder that Muggsy’s career assist-to-turnover ratio - an incredible 4.7-to-1 - is the best of all time among players to average at least five assists per game.

I don't know if we'll ever see anyone quite like him again, but there have been plenty of players over the years who've channeled his spirit by finding ways to weaponize their small stature.

Ten years after pint-sized guard J.J. Barea helped swing the Finals in favour of Dirk Nowitzki and the Mavericks with his shiftiness and chicanery, another 5'10 waterbug is playing a key role next to another paradigm-busting big man on a championship hopeful. With Nikola Jokic's Nuggets down four rotation guards, 30-year-old rookie Facundo Campazzo has stepped into the limelight and helped keep Denver's high-wire act in balance.

Campazzo is a genius playmaker, with panoramic vision and a penchant for threading darts through narrow corridors. His assist-to-turnover ratio isn't quite Boguesian, but at 3.2-to-1, it's still one of the best in the NBA. And unlike a lot of the players who tend to comprise the league leaderboard in that statistic, Campazzo's passing doesn't lack for audacity.

His singular ability to spy openings between thickets of trees can be as valuable as others' ability to see over them. So, fine, Campazzo can't throw passes over the top the way Jokic or LeBron James or Luka Doncic can. He'll just drop a behind-the-back bounce pass under your arm or send one whistling past your ear instead.

Campazzo is also a deceptively disruptive defender, relentless and difficult to shake. While his size clearly limits the impact of his shot contests, he's at just the right height to dig and swipe and mess up an opponent's dribble. Getting him to run flush into a pick is damn near impossible, like trying to set a solid screen on a cat. And off the ball, he's a hidden prowler, disappearing in the tall grass before pouncing on unsuspecting passers and ball-handlers who literally don't see him coming.

Is he destined to get hunted and exposed in the playoffs? Maybe. He's still extremely limited as a scorer, and it's probably not a good thing that the Nuggets are as reliant on him as they are. But I'm looking forward to watching him navigate that treacherous terrain. Short guys finding workarounds to their physical limitations provide some of the NBA's greatest displays of resourcefulness. Necessity is the mother of invention, after all.

Folk - The Short-Roll

My fixation with the short-roll is a two-headed monster that adjoins and separates depending on what side of the floor they occupy: Lucas Nogueira and Kyle Lowry. Nogueira, the gone too early short-roll savant, paired with Lowry for some of the most beautiful and penetrating pick n’ roll short-rolls and lobs in Raptors history. Lowry, the most potent partner of Nogueira’s offensively, but a novel defensive quarterback and mover; a player who harnessed his physicality and maximized it in a way that few players do, and a marvel who became an immensely affecting paint defender despite the aforementioned physical attributes. Lowry went on to carve out a HOF resume after Nogueira’s departure (and retirement), but those two had an undeniable neural link that led to some of the most inspired improvisational basketball that I’ve ever seen.

The NBA has changed, obviously, we all know that. The landscape of “big man attributes” has gone through a transformative phase, and what’s left are big men who are - on average - less capable of rote, practiced post moves and are more capable of incorporating a live dribble, extended shooting range (although, the stretch 5 is still a lot rarer than most think) and naturally, playmaking on the move. The All-Star Weekend’s skills competition isn’t proof on it’s own, but it does point to the changing landscape. Short-rolling is part and parcel of the new and improved ‘modern big’. However, it’s still underappreciated and underdeveloped relative to the other skills that are considered staples of said ‘modern big’.

Yes, teams were terrified of Steph Curry or Kevin Durant coming open off of a screen in the pick n’ roll, but there were few things more deflating than a hedge or blitz that failed to eliminate the pocket pass, and Draymond Green cruising to the bucket with ball in hand and a baseline cutter hard charging the paint. And if the defender on the weak-side tags the cutter, then the pass finds the corner shooter. It’s death, all of it. The nightmare fuel of the Warriors unstoppable run, and the reason the Rockets tried to flatten everything out above the break against them.

Curry and LeBron James have warped how we see playmaking. Curry, for his ability to distort and warp defenses that benefits his teammates in a way we might never have seen before. James, for his ability to leave defenders flat-footed because he read the pre-rotation and beat it. The 40 mile per hour skip passes that take a more dangerous arc because of his height. Still, playmaking from the middle of the floor is very dangerous. It fueled the Heat’s run to the Finals last season, because it’s adaptable and hard to scheme against. Bam Adebayo and Jimmy Butler catching the ball and evaluating with the whole floor in front of them and the proximity of the basket even closer, that burned teams. The Raptors, who employ ball handlers who don’t typically gain much of an advantage from turning the corner towards the paint (save for Lowry in the playoffs, what a man) baked in heaps of short-rolling opportunities for their bigs to manufacture pressure in the middle that wouldn’t have been there otherwise. Serge Ibaka, ever the mid-range release valve. Marc Gasol, the passing genius. And prior to their arrival, the wonderful ‘Bebe’.

Now, not every big man possesses the attributes to succeed in the short-roll, and Lowry hunts them down.

Lowry’s use of verticality (particularly while defending the fastbreak) is worth it’s own deep dive, and maybe we’ll do that down the line, but I think his greatest defensive feat is his ability to wield the charge as a means to defend the paint as a sub-6-foot guard. It’s a fantastical application of his defensive ‘feel’. For the ultimate piece on feel, click here. Try to remember how many times you’ve seen a big man catch the ball on the roll and the guard in waiting provided no resistance - it’s really common. Lowry’s ability to read developing plays, and beat big men to their own spot has led to countless plays where the short king, Kyle Lowry panicked big men in the paint. More often than not, Lowry takes a charge or converts a full on rim-run into a short-roll. That’s right, he loves it on offense, and dictates it defensively.

Lowry turns players away from the paint, forces counters, and elongates offensive possessions from the backline better than virtually any guard has ever done before. The cohesiveness and coverage of the Raptors defense has slipped this year, but Lowry’s uncanny defensive fortitude at the back end allowed the Raptors to play fast and loose with a lot of coverages that were instrumental in building a defense that won a championship, and many more successful ones prior to that. Taking heaps of charges, and dictating that uncoordinated and out of control big men suddenly become controlled, intelligent passers (it usually went his way). A short king indeed.

Zatzman - Fred VanVleet

One of these things is not like the other.

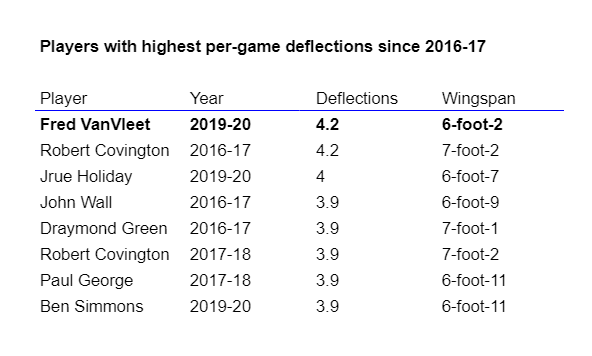

NBA Advanced Stats only has deflection stats going back to 2016-17, so this is all the historical data we’re gonna get. And there’s a clear outlier at the very top of (recorded) history. While most of these players have wingspans ranging near or at seven feet long, VanVleet’s is a miniscule 6-foot-2, only slightly longer than his height. But last season isn’t his only entry onto the list; VanVleet currently leads all players this season with 3.8 deflections a game.

So how the hell does he get so many deflections?

If anyone in the NBA channels the powers of Ant Man, it’s Fred VanVleet. There’s a number of reasons why VanVleet is such a master of disruption, and the list is common among all good defenders; he’s smart, and he’s fast, and yada yada. That’s normal stuff. VanVleet has those skills in spite of being short, not because of it -- or at least they’re unrelated to his size. But the uniqueness of VanVleet’s defensive savance is, counter-intuitively, his strength.

Ant Man is short. Famously so. That’s more or less the extent of his superpower. He retains the strength of a normal-sized man in his abnormally sized frame. That’s much the same as VanVleet’s incredible defensive superpower. He may be dramatically shorter than the average NBA player, but he is as strong or stronger than most of them.

It doesn’t matter how big you are; you can’t go through him in transition.

When gargantuan NBA bigs catch the ball on the roll and see a point guard in their way, the result is usually a foregone conclusion. Not so when it’s VanVleet. He can even wrestle with opponents’ other bigs before rotating over to protect the rim.

NBA teams often ask a weakside defender to sink into the lane in team pick-and-roll defense. Actually doing anything productive when they’re there is a tall order for guards, but VanVleet is comfortable on an island against legitimate seven-footers. Just hit them before they hit you.

Even when it’s not in the scheme, VanVleet realizes when his man cuts into the wrong space, and he will improvise and jet into the lane, outwrestling players with 50 or more pounds on him.

Even when the largest players in the league carom into him, VanVleet somehow ends up with the ball. Here VanVleet actually manages to come up with the ball because of his height.

What do all of those plays have in common? Among other things, opponents’ absolute inability to move VanVleet. The man doesn’t budge an inch. Sure, you could say part of that is because of his low center of gravity. More than anything else though, it’s because the dude is Hercules strong. If everyone in the NBA looked the same, it would be the league’s loss. There’s no replicating players like VanVleet.

Share this post