People usually lose the tiny sliver of the present in the infinitesimal gulf of the past, the yawning chasm of the future. How could we see a dot, ever obliterated by what it holds up, what it feeds into?

For the NBA, that means we are full of misconceptions of the now. People see a league in such a supercharged state of change and so see yesterday as today. If you try to snap a still frame, you can miss and end up grasping at its wake. That’s true in the micro, why it usually takes a year after players change their stripes for their reputations to follow, why lots of players who haven’t yet made the grade are considered stars because they one day may become one. But it’s true in the macro, too. Strategies that worked the year before can be old hat by the time a new season rolls around, or team leaders can try to innovate years before the tactic will actually work.

We wrote in the 2020 NBA Playoffs about the various futures of the big man in the NBA, about the possible visions of the role and the stars and hard-hitters who fulfill them. But any controversy about the value of the NBA big was laid to rest during that same playoff run as Anthony Davis ate the world, and then Giannis Antetokounmpo did the same the following postseason.

Now it’s the wing who is misplaced, who lives out of time in the general understanding of the NBA. It’s not that people misconstrue the value of the wing, it’s just that time shifts too quickly, like quicksand. Well, that and the fact that people misconstrue the value of the wing.

Wings don’t rule the league anymore. They’re far from extinct, but you can’t just throw an elite wing -- or even two! -- on the floor every night and expect to win. Too much has changed for that to be true.

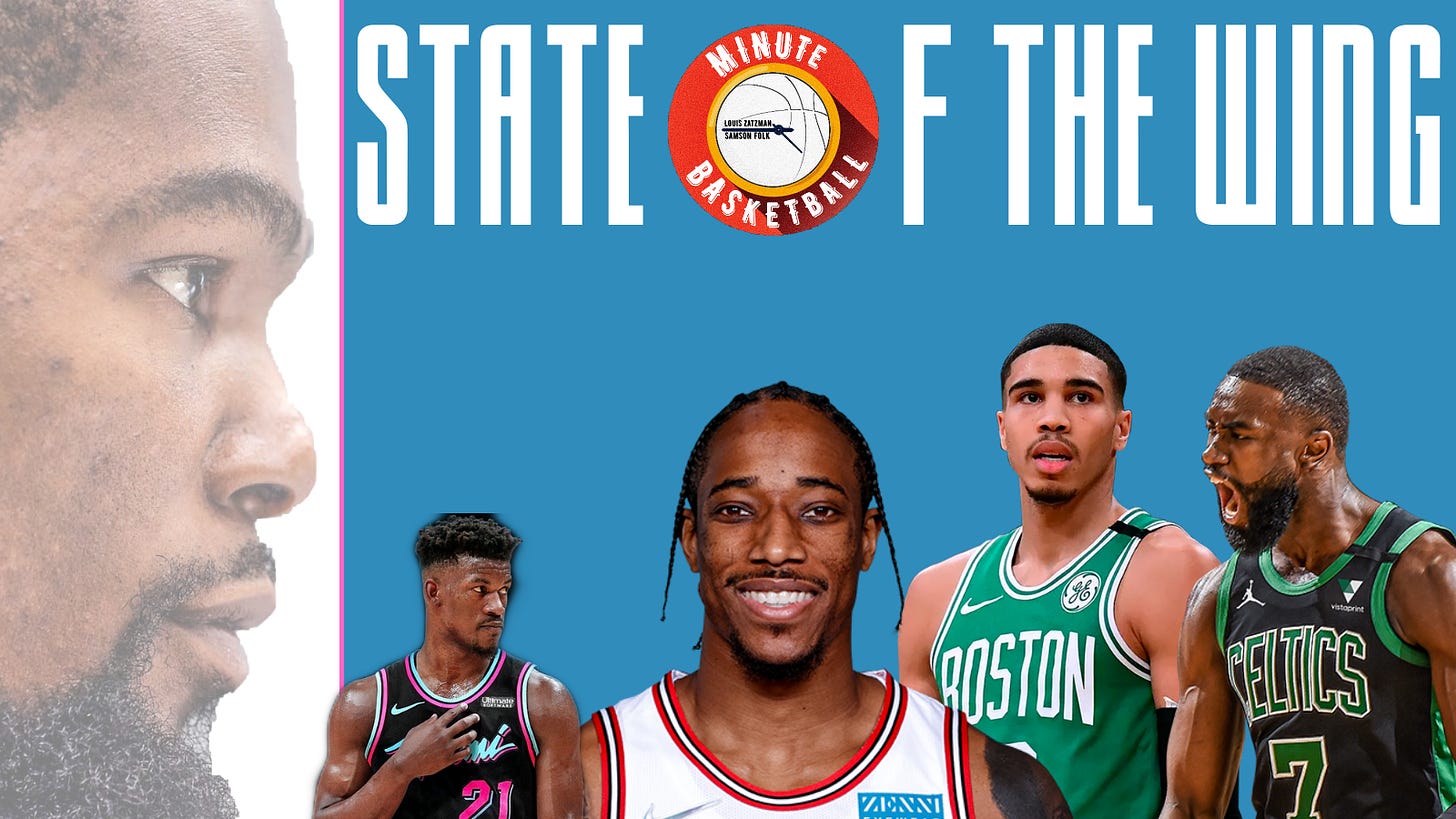

This week in Minute Basketball: The State of the Wing

Zatzman -- The Celtics, lost in time

Sometimes when you take a risk in building a team for the present -- and sacrifice the multiplicity of possible futures that once were available to you -- you lose the pot when the present shifts under your feet.

That unenviable position is where the Boston Celtics find themselves this year. Just two short years ago, the Celtics started the season 11-2. Smart, plugged-in writers were calling the NBA a “wing-dominated league” and Jaylen Brown and Jayson Tatum maybe “the best young duo of them all.” Tatum played in his first All-Star Game that year, and Brown joined him the following season. Both averaged over 20 points a game, dominating in isolation, in the pick and roll. Both were elite defenders. The league was in the palm of their hands.

Boston lost in the playoffs that year to an (I still believe) inferior Miami Heat team. The following season -- despite continued excellent play from Tatum and Brown -- the Celtics were a .500 team. Now this year they’re 5-6, still stymied by a pathetic offense. More or less, they’re proving that last season’s .500 record was their true state, rather than a fluke.

Yet Brown is playing the best basketball he’s ever played, scoring more points than he ever has, and on better efficiency to boot. Tatum has seen a drop off, but he’s scoring almost 24 points a game to complement Brown. The two remain a star duo. The best in the league? No, absolutely not. But a wonderful one regardless.

So then what’s going on with the Celtics? More or less, exactly what was going on with them before. That might be the problem.

The Celtics are taking a similar diet of shots as they were last year and the year before, with few attempts at the rim and plenty of jumpers from midrange and from deep. (That mimics the output of another wing-heavy underachiever in the Los Angeles Clippers.) The Celtics are one of the most isolation-heavy teams in the league, but that was true of them in 2020-21 and 2019-20. They’re posting up a lot more than they used to -- but that’s actually one of the most efficient components of their offense this season! They’re in the midst of a small shooting drought, but that’s a normal thing that happens to every team during the course of a season. Good ones win regardless.

And make no mistake, the Celtics were a good team in 2019-20. Even though the team is more or less the same at heart -- perhaps even more dedicated to their identity now -- they’re far from a good team now. That’s what happens when the context changes around you. Defenses now are smarter and more variable, trap more aggressively, switch more often. Hero ball became heliocentrism, but the latter only works when the center of the universe is also one of the best passers in the league. Without that ability, what once worked 50 times a game, 80 games a season, now only works 30 times a game. That adds up.

You can’t subsist on hard shots in the regular season. You can jerryrig it to work, maybe, in the playoffs, when that’s all you’re gonna get anyway. But in the regular season you need a diet of comfort, a little bit of breakfast-for-dinner every now and then. And Boston makes everything hard for its stars. Both take around 40 percent of his shots in the midrange. They can make those shots -- but that’s subsisting on the hard stuff. And the other Celtics have gotten worse at converting into easy points the advantages Tatum and Brown create. It’s not that the two are bad passers -- in fact, they’re both very good at that, if not world-bending. But the team lacks advantage extenders. Evan Fournier, Kemba Walker, Gordon Hayward: all are exquisite at that very skill. They made quick decisions, attacked rotations, and maintained whatever their teammates created. Without that, the real benefit of having star players who can initiate in isolation, the pick and roll, or the post is blunted. In other words, wings can’t do it all alone.

That same smart writer in 2019 wrote that “the best version of this team is still a couple of years away.” That would have been true if all things remained the same. But they haven’t, and so the Celtics have lost whatever cache they built over the past half decade, have fallen by the wayside of progress, are doomed to conquer a league that doesn’t exist anymore.

Folk - Coup D'état

French for “blow of state”. A seizure and or removal of a government and its powers. Louis and I still hold fast to our thoughts on “The state of the big”, and by proxy of other factions being underrated, the ‘wing’ faction seems destined to be overrated at this moment in time.

Why did the wing become the home of superstars and Finals MVPs? Why is it the most likely to reward the players who occupy it with exorbitant contracts? Wings are supposed to be the perfect marriage of guards and bigs. An emulation of guard skills on offense in a bigger body. True offensive engines. And defensively, capable of the weak-side rotation and block that few guards ever make happen, and still capable of stepping out on a switch and stonewalling some of the NBA’s most agile ball-handlers. Yet, the latest Finals MVP, Giannis Antetokounmpo delivered a championship to the Milwaukee Bucks by leaning harder into the ‘big’ aspect of his game. Defensively, he’s not at the point of attack. Offensively, he’s not initiating offense, but finishing it. Dubbed as a wing who could play point guard upon his arrival in the NBA, Antetokounmpo found success elsewhere.

Is the NBA’s fetish with wings subsiding a bit? Not for Henry Ward, or for the Toronto Raptors - the Secretary of the State of the Wing, and the militant branch of the State of the Wing. The landscape of wings in the NBA is changing, both at the top and the bottom. When Michael Jordan was everything in the NBA, the world waited with baited breath on the next version of him. A popular comparison at draft time for years (but no longer). LeBron James has dominated the NBA’s news cycle and so he became the archetype for “best.” The wing became supreme because it was adjacent to James - Adjamescent. This isn’t to say that James can’t claim supremacy on certain nights, but that his grip hold on the NBA has certainly slipped somewhat. And with that, the optics of the wing archetype are destined to change.

All-Star games will still likely be the playground for wings. It’s also likely that Louis’ aforementioned tandem from Boston makes waves in this year's version of it. But, when we look at the top 4 teams in the west, what All-Star wings can be found on their roster? A betting man would say none. And in the east? Jimmy Butler and DeMar DeRozan continue to beat All-Star drums, but they’re certainly part of ensembles. Kevin Durant sits atop the Nets, lonely, but averaging 30 points a game. Eagerly waiting for his non-wing co-star to catch up. The only wing capable of truly carrying a team right now also happens to be, probably, one of the 10 greatest players to ever touch a basketball.

I am a prisoner of the moment. It’s early. But, now seems like a clear point of rest, to stop and look at the state of the wing, where it was and where it’s headed. For now, the aforementioned trio of DeRozan, Butler, and Durant continue to hold the line. A platoon of the best, waiting for reinforcements (Paul George and Kawhi Leonard), desperate to avoid the coup.

A spotlight for DeMar

DeRozan, who was under qualified to carry the mantle of the Spurs dynasty, but succeeded in his own way, for his own game. Now, far removed from the expectations of toppling LeBron James for the ‘North’, and sitting amongst an immensely talented cast of teammates, DeRozan has translated the simplest aspects of his game directly to the Bulls roster - a roster that is un-gelled and in desperate need of DeRozan’s particularly straightforward playstyle. 2-man actions with Lonzo Ball, post-ups, iso’s, pick n’ rolls that players go under on, that immediately lead to re-screens and a barrage of accurate mid-range jumpers. The unfathomable shooting percentage against tight contests. Graceful pirouettes through the paint that would sooner land him in the Bolshoi Ballet than a basketball team, and the impossibly placed tungsten cube in his foot that anchors every pivot of his deep into the earth. The Bulls defense has insulated DeRozan, and in turn he has floated their offense to the tune of 27, 5.5, and 3.5 on absurd efficiency.

“You can sink and drown, or you can stay afloat. And we’re out here like Michael Phelps.” - DeMar DeRozan

Floating the Bulls, and wing supremacy - at least a bit.

Share this post